In the run up to the COP21 UN climate talks in Paris this December (more here on how to join us and take action), we’re busting some commonly-heard climate myths, from big business being part of the solution to putting our faith in techno-fixes. Catch up with last week’s mythbuster – “The EU is leading the way”.

Comments or questions about this article? Come and find us on Facebook and Twitter.

The myth

When lack of progress is evident at the international climate negotiations, and finding common ground for a deal seems impossible, we often hear the same tune: “an imperfect agreement is better than no agreement.” This line of argument is usually used to bring down ambition, to push for the lowest common denominator.

As the UN climate talks in Paris (COP21) draw nearer, and concerns that a deal won’t be reached are on the rise, we are hearing this myth more and more often from politicians and the mainstream media. “We can’t expect too much. It’s complicated. Close to 200 countries are negotiating. A perfect agreement is impossible. Perfect is the enemy of good”.

This year, the tune is also louder than usual. The COP 21 will be French president François Hollande’s only major international summit, and he is intent on it being a success. This is why the French government is going out of its way to make an agreement happen: drafting new texts, minimising the lack of progress, urging nations to find common ground… Recently, Brice Lalonde, United Nations Assistant Secretary-General, went as far as to say that the substance of the agreement was less important than obtaining an agreement itself.

We’ll try to break this myth down, to show how this idea is not only absurd, but also used to push for less ambition and unfair texts and mechanisms.

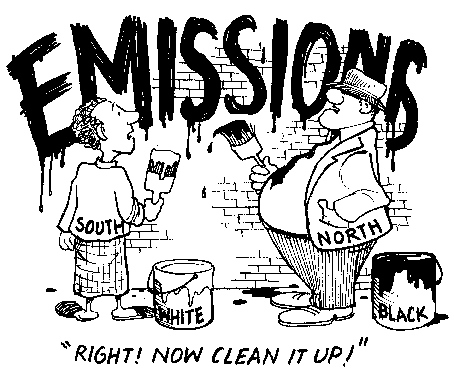

1. The core principles of the Convention are being betrayed

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) which was adopted in 1992 is based on the principles of equity and common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities. This means that developed countries (i.e. the Global North) have an increased responsibility to act on climate change, as all countries are not equally responsible for climate change. These principles were embedded into the Kyoto Protocol, which is currently the only international legally binding document for climate action. The Convention also includes other elements like technology transfer, climate finance and capacity building for developing countries (Global South).

The current draft agreement, which will be used as a basis for negotiations at COP21, goes against these principles – after years of work from the part of developed countries to evade their historical responsibilities and to shift blame to developing nations. These countries are even going as far as to say all countries must reduce emissions equally.

The draft agreement does not capture the complexity of the issue of climate change, as developed countries are pushing for emission cuts (“mitigation”) only, and are less keen to talk about adaptation, finance, loss and damage or technology transfer – even as these issues are crucial to developing countries most impacted by the first effects of a warmer planet. But as developed countries dominate the UN climate negotiations, these elements are constantly pushed to the bottom of the agenda – and the draft agreement for Paris is no exception. Can we accept such an agreement ? Our answer is no.

2. Two degrees is an imperfect – and dangerous – objective

The main objective that was agreed on at the climate talks in Copenhagen (2009) – to keep global average temperatures under 2°C – was already a compromise, the “highest” common denominator. Although the common objective of 2°C has helped raise awareness about climate change globally, it is in fact a dangerous level of warming in itself. It will have devastating consequences for many poor and vulnerable countries.

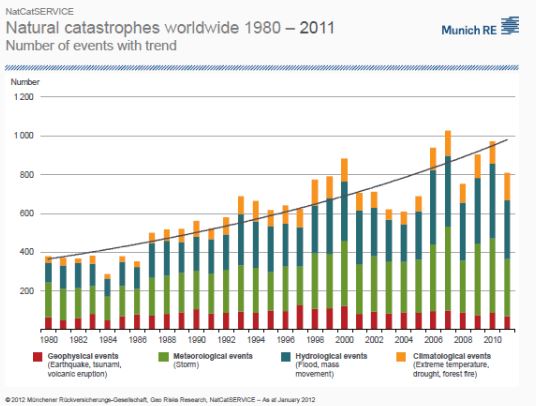

In 200 years, we’ve managed to raise the average global temperature by 0.85°C. As greenhouse gases accumulate over time, extreme weather events have tripled in the last 30 years (see the graph below).

These are not just numbers, these are very concrete, devastating events, bigger and stronger than we’ve ever seen. The strongest hurricane (possibly) ever was recorded last week in Mexico. Yemen has experienced a hurricane for the first time in human history. Permafrost is thawing and releasing methane at “unbelievable” rates according to scientists. The Arctic is melting faster and earlier than what was expected just a few years ago. We are already living with climate change.

Less than a degree of warming has brought about dire and unpredicted consequences. And many experts are telling us we might just have crossed the dangerous thresholds where feedback mechanisms are initiated and climate change feeds itself, thus becoming unstoppable.

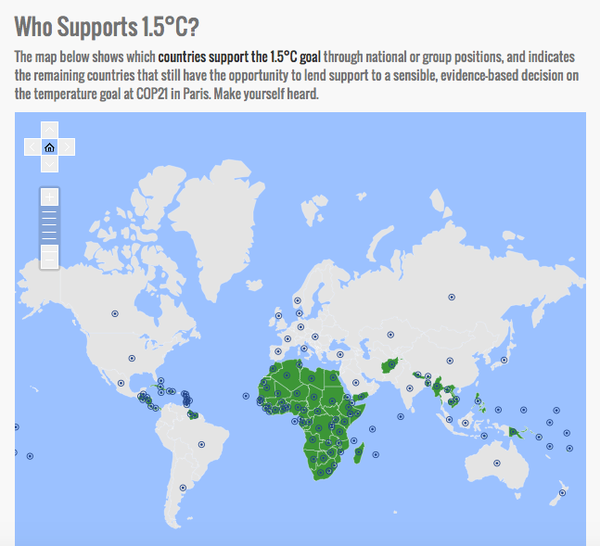

Lower political ambition is the equivalent of playing Russian roulette – but in this case, the ones holding the gun aren’t the ones taking the biggest risks: +2°C conceals huge disparities in vulnerabilities to climate change between countries. Many developing countries can’t afford that level of warming, and this is why more than a hundred countries in the Global South have never given up on their initial goal of keeping temperature increase below 1,5°C. In fact, a new campaign has been launched at the climate intersessionals in Bonn to defend this more ambitious objective at the COP21. Unsurprisingly, the most vulnerable nations to climate change are the ones advocating for more ambition, as the map below shows.

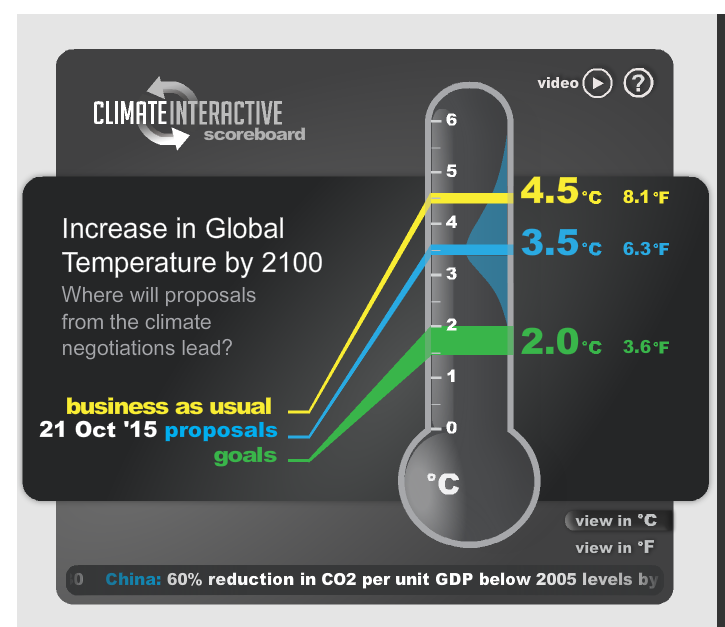

Moreover, vulnerable nations are actually doing more than developed countries. According to the new civil society equity review of INDCs (Intended Nationally Determined Contributions for domestic emissions cuts) i.e. voluntary climate pledges, developing countries are pledging to cut emissions more than their fair share is, while rich nations are pledging much less than is required, as we highlighted in our 2nd myth buster. The review concludes that together, the commitments captured in the INDCs will not keep temperature increase below 2°C, much less 1.5°C. Even if all countries meet their INDC commitments, the world is likely to warm by a devastating 3°C or more.

The conclusion is simple: we need urgent and ambitious action by developed countries, which requires a fair process and fair outcomes. Read more about the civil society equity report.

3. The argument is used by developed countries to push an unfair agenda

As we explained earlier, developed countries are intent on minimising differentiation when it comes to reducing emissions, and in doing so challenge the core principles of the UNFCCC. Their goal for Paris is a new mitigation-focused agreement that is weaker for developed countries than the Kyoto Protocol, more burdensome for developing countries, and that excludes meaningful commitments on adaptation, finance, technology transfer and capacity building for poorer countries. This is evident from the long-term global goal for emissions cuts by 2050 or 2100 that many countries in the Global North are supporting and which is being pushed to be included in the Paris agreement.

The problem with this, aside from the fact it erases historical responsibility, is that it doesn’t meet the carbon budget, a finite amount of carbon that can be burnt before it becomes unlikely we can stay below irreversible warming, which will expire in just a few decades. It’s delaying action and shifting focus from the pre-2020 and 2020-2030 goals. Moreover, some terms that are used to describe the long-term goal include “net-zero” and carbon or climate “neutrality”. This is particularly problematic because it’s not in line with equity: it does not define an emissions reduction pathway, and doesn’t necessarily mean a complete transition away from fossil fuels. It also opens the door for dangerous technologies. Read more here on why “net-zero” as a global goal is problematic.

4. An agreement doesn’t guarantee implementation

The Kyoto Protocol isn’t a perfect agreement, primarily because it contains market based “flexible mechanisms” like the Clean Development Mechanism and International Emissions Trading, which help countries meet their targets without actually reducing their own emissions. But even with its flaws, it’s the only existing international legally binding agreement for reducing emissions nationally (to give an idea of the current lack of progress in the UNFCCC, it’s still unclear whether the Paris agreement will be legally binding or just another empty declaration).

International law differs from national laws in the sense that they cannot be enforced. When countries don’t respect their commitments or backtrack, there are no repercussions. You can’t guarantee that what’s promised is what you’ll get. For example, the United States never ratified the Kyoto Protocol. Canada withdrew from the Protocol in 2012. In Warsaw, in 2013, Japan abandoned its initial plan to cut emissions by 25% by 2020 and announced its new target was an increase of 3.1% – civil society and delegates were stunned. An agreement on paper doesn’t mean it will be respected later, and diluting ambition in texts can be a slippery slope.

5. A bad agreement would lock us into unambitious action

An unfair legally binding agreement would lock us into weak policy and unambitious action. This would mean crossing tipping points that set us on track for catastrophic climate change, a death sentence for the most vulnerable nations and frontline communities.

A weak agreement would also create the illusion that we are taking action sufficiently, which would also have a negative effect on national climate policies.

We cannot afford to delude ourselves. We can no longer make excuses. We refuse to believe a bad agreement is better than no agreement. Ambition cannot be sacrificed by any means.

Read more on what we can expect in Paris and why the COP21 will not deliver.

To conclude

What good is an agreement that doesn’t curb climate change in a meaningful and equitable way? What’s the value of an agreement that puts us on course for irreversible climate change? The UNFCCC process is more than 20 years old. Can we really accept watered-down deals to come out of it? Or is it all the more reason to expect an agreement that’s up to the challenge?

Achieving an agreement is not the end goal, tackling climate change is. The content of the agreement is crucial: we need ambition, and we demand fairness. We won’t settle for anything less. Perfectionism isn’t holding back the climate talks, a clear lack of political will is.

Furthermore, it’s important to underline that focusing solely on climate negotiations won’t save us. Up until today, climate negotiations have only replicated or even reinforced global power dynamics as rich nations dominate the UNFCCC halls. That’s why we need strong climate justice movements, in every country, to put pressure on our governments, not just once a year during the UN climate talks but all year round. Citizens and communities around the world have been fighting dirty energy projects and implementing solutions for decades. There have been many inspirational victories – from Nigeria, to Croatia, Scotland, France and Palestine. Governments of developed countries need to take notes from the people who already have the solutions to the climate crisis.

We have been patient enough. We will demand true justice in Paris, and we will continue to show the strength of our movement well beyond the climate talks.